Balancing the demand for increased service quality, control and sustainability with the need to maintain a decades-old transmission and distribution infrastructure is the challenge of grid modernization. The changes enabled by new technology may ultimately redefine the traditional utility business model. A range of industry activity is occurring as stakeholders grapple with these challenges.

Diverse catalysts for change

“In some states, like New York, grid modernization initiatives are being driven by the governor’s office,” says Todd Horsman, Director of Regulatory Affairs at Landis+Gyr. “In other cases, the public utility commission is taking up the gauntlet to drive change.”

In Minnesota, Horsman says, it’s entirely driven by the utilities, where they actually forced the public utility commission to drive change. The e21 Initiative in Minnesota was an outgrowth of efforts by utilities in the state to learn how they can work with regulators to reinvent the utility business model and develop a customer-centric framework to remain financially viable.

The collaborative e21 effort brought together stakeholders from utilities and the private sector to agree on policies supporting grid modernization. In a state that has not experienced the explosion in solar seen in the Southwest, Minnesota has produced surprising advances in solar valuation and performance-based rate design—and it’s also moving into the business of renewable energy.

“They just approved their first community solar project,” says Horsman. “I definitely think you’re going to see that project start to take off.”

In Massachusetts, where former governor Deval Patrick’s office drove grid modernization efforts, utilities were required to submit plans last year. Proposals submitted by the state’s investor-owned utilities included installation of advanced metering in every home, opt-in time-of-use rates and the development of a Distributed Energy Resource (DER) Management system.

Hawaii, which has set the nation’s first 100-percent renewable portfolio standard (RPS) by 2045, has acknowledged the strategic role of grid modernization in enabling utilities to meet that aggressive, non-negotiable goal.

Top Ten State Leaders

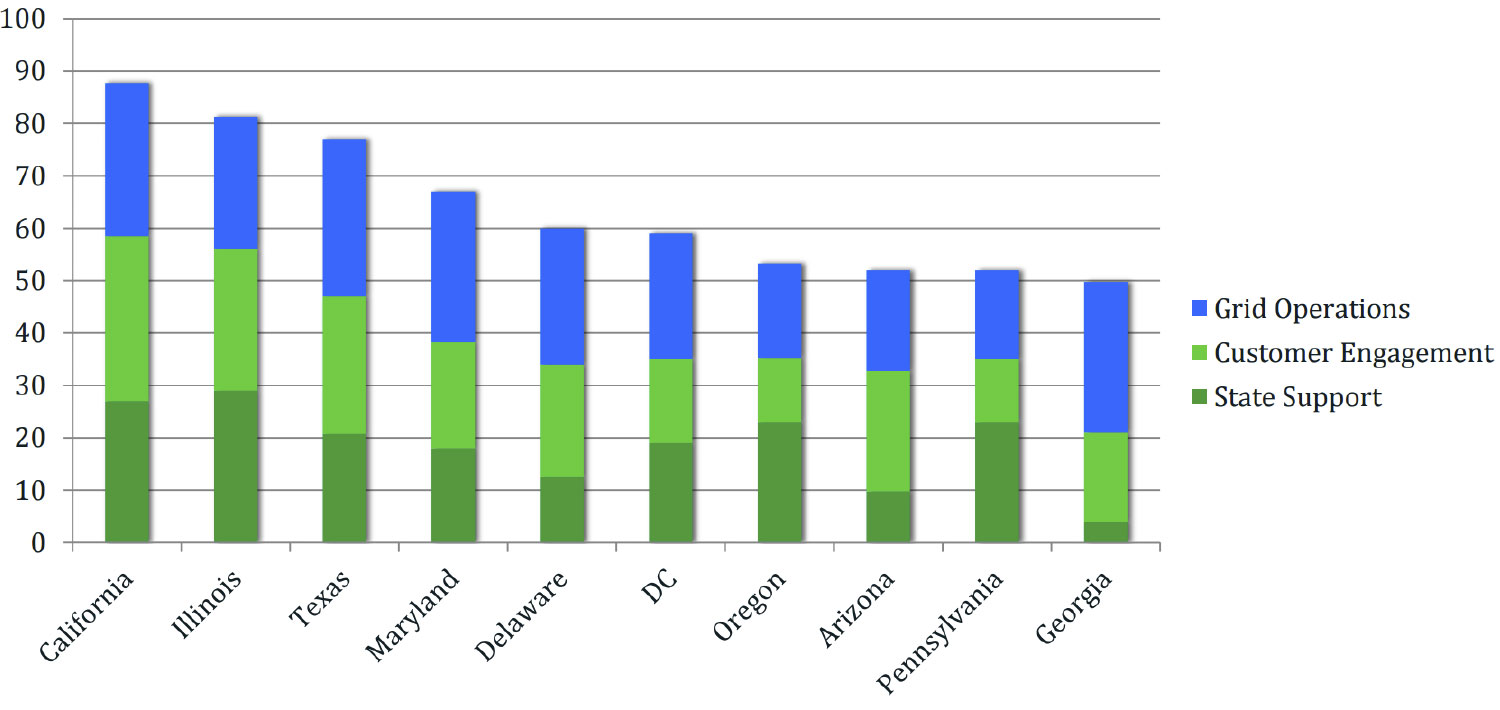

The states of NY, MN, HI and MA illustrate the many ways utilities are adapting to change and moving toward new business models. However, there are several states where grid modernization is well under way. A recent Grid Modernization Index released by the GridWise Alliance, an organization that supports the integration of new grid technologies, and Clean Edge, an energy research and analysis firm, analyzed the top states where grid modernization is taking place (see chart) and leading the rest of the country.

The states of NY, MN, HI and MA illustrate the many ways utilities are adapting to change and moving toward new business models. However, there are several states where grid modernization is well under way. A recent Grid Modernization Index released by the GridWise Alliance, an organization that supports the integration of new grid technologies, and Clean Edge, an energy research and analysis firm, analyzed the top states where grid modernization is taking place (see chart) and leading the rest of the country.

A number of factors contributed to California’s top position on the list. A good example is the new business model launched by Southern California Edison, as part of its Local Capacity Requirement, which includes a generation mix of central power plants, solar and other distributed energy resources (DERs). This enabled the utility to replace a decommissioned nuclear power plant and several natural gas-fired power plants.

In Texas, the state’s Distributed Resource Energy & Ancillaries Market (DREAM) Task Force introduced a concept for grid modernization that also includes participation of distributed resources in wholesale markets, along with ancillary services.

Top 10 Results

New York’s REV – A New Utility Business Model

While many states are well ahead of New York in their grid modernization efforts, the Empire State is unique because of its comprehensive approach to completely changing the utility business model.

In New York, Gov. Cuomo’s Reforming the Energy Vision (REV) strategy for building a clean, resilient and affordable energy system includes aggressive targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent from 1990 levels, obtaining 50 percent of the state’s generation from renewables and reducing building energy consumption by 23 percent—all by 2030.

“As part of their reform efforts, they’re actually taking a look at the business model,” says Horsman. “They’re seeking a new model for earning revenue, away from setting rates and earning money by the kilowatt-hour; whereas, with the rest of the states, the business model is remaining roughly the same.”

Lisa Frantzis, Senior Vice President, Strategy at Advanced Energy Economy (AEE)—a national association of business stakeholders dedicated to making the global energy system more secure, clean and affordable—agrees. “A lot of states are focusing on rate design issues and New York is probably one of the few that is really tackling the business model issue, or how the utilities make money,” she says. “What New York is trying to do is shift the utility incentive structure to reduce investments in CapEx and focus more on operating expenses that increase the role of DERs.”

No “One Size Fits All”

As utilities and state policy makers continue to search for ways to meet environmental targets, manage slowing load growth and maintain long-term utility financial viability in a rapidly changing environment, it is clear that there will be no one-size-fits all solution.

As utilities and state policy makers continue to search for ways to meet environmental targets, manage slowing load growth and maintain long-term utility financial viability in a rapidly changing environment, it is clear that there will be no one-size-fits all solution.

“It’s not business as usual anymore,” says Frantzis. “It’s no longer one-way power flow. Now there is power generated from DER assets that are putting power back into the grid. There’s more demand for resiliency, more service options and requirements for environmental sustainability. In addition, you have a lot of aging infrastructure that needs to be replaced. All of this is converging and driving business model changes. Utilities across the nation are recognizing the need for changes.”

Frantzis notes that while some states are moving slowly, states like New York recognize the need for a significant shift to address utilities’ long-term financial viability. “By encouraging innovation and expanding the role of third parties like Landis+Gyr and others—and engaging customers more—the industry will be better able to sustain emission reductions and create a more flexible, resilient grid that can accommodate higher levels of DER,” she says.

“It’s going to take time, there will be no easy solution. It will be different in each state. And that’s the challenge ahead of us.”

The Clean Power Plan: A Federal Accelerator for Grid Modernization

The Clean Power Plan (CPP)—the first set of standards for reducing carbon emissions from existing power plants, finalized by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) last year—is a potentially significant business driver for grid modernization. “It’s probably the biggest initiative that will drive states to actively make changes,” says Landis+Gyr’s Horsman. “And it affects all utilities, even co-ops that are self-regulated.”

The CPP set state-by-state targets for carbon emissions reductions, with a national goal for the electricity sector to reduce emissions by 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

Over the last decade, power sector emissions have dropped substantially as the costs of natural gas and renewables plummeted. As such, the CPP is “tracking things that are happening in the market anyway,” says Matt Stanberry, Vice President of Market Development at AEE. “It’s just accelerating the pace of that change.” So while the Supreme Court placed a hold on the CPP on February 9 until the litigation process is complete, these market forces will continue to drive change.

According to Stanberry, the CPP increases the focus on the importance of emissions reduction and, in so doing, strengthens another significant driver for the deployment of grid modernization technologies. “And because the states are actually the implementing bodies for meeting the emissions targets, the CPP represents a partnership between the states and the federal government,” continues Stanberry. “It involves almost all of the relevant regulators in integrated energy and environmental planning.”

A greater focus on emissions reductions will act as another powerful force in the industry’s need to consider new utility business models.

Snapshot of a New Utility Business Model

New York’s REV is considering various long-term approaches that shift away from traditional utility revenue sources and cost recovery. These mechanisms are still under discussion.

New York’s REV is considering various long-term approaches that shift away from traditional utility revenue sources and cost recovery. These mechanisms are still under discussion.

- Modified Net Plant Reconciliation Mechanism – Infrastructure savings: utilities would keep revenue until the next rate case, from avoided CapEx that would otherwise be “clawed back” by the commission, if it is invested in broadly defined DER solutions.

- Earning Impact Mechanisms – Earn performance-based incentives based on multiple categories aligned with REV objectives—such as interconnection of distributed generation, energy efficiency, peak load reduction, customer engagement, affordability, and data access.

- Market-Based Earnings – Charge fees for services enabled by new energy distribution platforms. For example, new fees for scheduling or dispatching of DG, microgrids and reliability upgrades (those not part of basic service) sale of data and analysis to third parties and other value-add services (retain revenue from advertising on customer portals, receive percentage of contractor referrals, etc.)