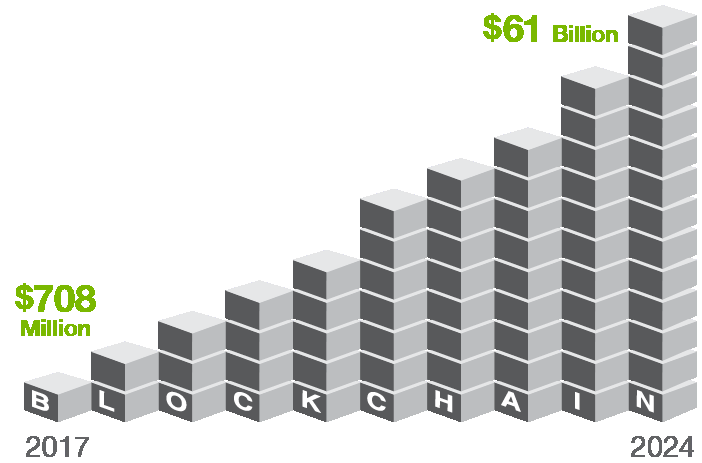

Wintergreen Research predicts that the global market for blockchain technology will grow from $708 million in 2017 to nearly $61 billion by 2024. Forget bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. They may have been the start of blockchain’s burgeoning popularity, but there are new applications on the way.

Wintergreen Research predicts that the global market for blockchain technology will grow from $708 million in 2017 to nearly $61 billion by 2024. Forget bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. They may have been the start of blockchain’s burgeoning popularity, but there are new applications on the way.

One Accenture study estimated that, by 2025, the world’s largest investment banks could slash their infrastructure costs by as much as $12 billion annually. Analysts at Gartner forecast that simple smart contracts — a technology enabled by blockchain — will be used by more than 25 percent of global organizations by 2022.

In the energy sector, more than three dozen corporate giants have joined the Energy Web Foundation (EWF), a global non-profit organization created by the Rocky Mountain Institute and Grid Singularity, a leading blockchain technology developer. EWF focuses on accelerating blockchain adoption across the energy sector. Utility companies in the group include Duke Energy, TEPCO, Swisspower, E.ON, PG&E, Exelon, and Sempra Energy.

These players are betting that blockchain will dramatically improve process efficiency, heighten cybersecurity, lower costs, and deliver real-time insight for energy-sector participants. “Blockchain technology has the potential to disrupt the way energy markets operate today,” said Dr. Frank Meyer, a senior vice president with E.ON in a recent press release covering his company’s association with EWF. “With this open accessible test platform, we can start to develop future market standards and build reorganized, more efficient ecosystems.”

Blockchain 101

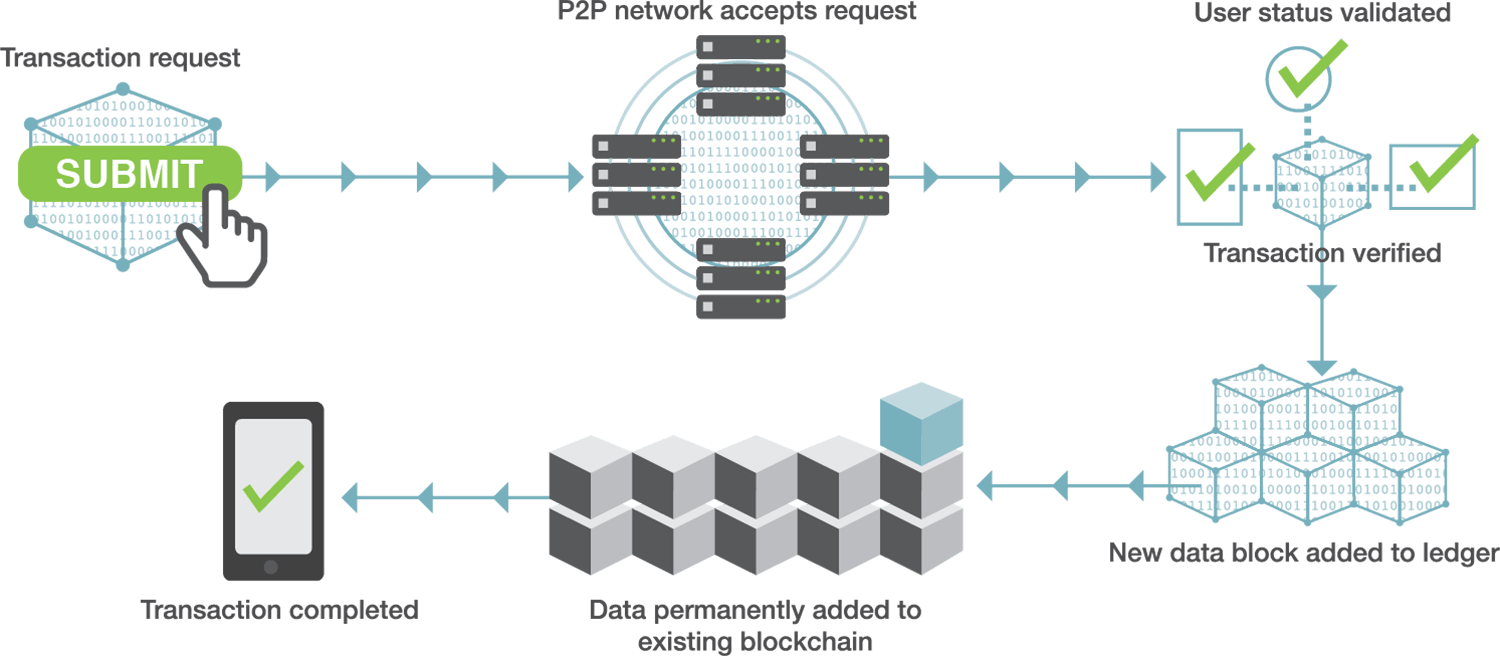

What is blockchain? It’s a digital and decentralized ledger that records all transactions. To enhance cybersecurity, the ledger encrypts records. It also processes transactions without a third-party provider, such as a bank, which eliminates verification delays as well as the cost of going through an intermediary who takes a cut of the deal. Cybersecurity, transparency, relatively low costs, and speed make blockchain well suited for energy trading.

In addition, the technology facilitates smart contracts, a form of condition-based automation. Simply put, a smart contract is software dictating that if “Circumstance A” prompts “Circumstance B,” the automation performs “Function C.” Gartner defines a smart contract as “a computer program or protocol that facilitates, verifies, or executes the terms of a contract.” According to the Gartner team, smart contracts have three characteristics:

- They operate on the decentralized ledger technology blockchain uses;

- They’re independent; and

- They can’t be changed or revoked.

These characteristics essentially enforce integrity and facilitate trust building. And, the contracts enable “market-based asset automation,” says Jon Creyts, Rocky Mountain Institute Managing Director, and Ana Trbovich, a co-founder of Grid Singularity. In an article published as part of this year’s World Economic Forum annual meeting, these authors explain that, “Smart contracts can be linked to energy-generating and consuming devices (such as wind turbines, rooftop solar cells, electric vehicle batteries, smart thermostats, water heaters), directing their behavior based on sensor-signaled energy prices and the physical state of the grid.”

Creyts and Trbovich add, “It is the fusion of these three blockchain characteristics — cybersecurity, low-cost transactions, and automation — that will allow us to integrate a grid of centralized power plants alongside distributed renewables, batteries, and flexible load, at minimal expense and without sacrificing reliability.”

To market, to market

Creyts and Trbovich also see blockchain as a means of simplifying the transfer of renewable energy credits (RECs). These credits are a tradable financial instrument that, like stocks in the S&P 500, have a wide range of values depending on where and when the renewable energy is created. Even the generation source impacts value, as solar RECs rise in U.S. states where regulators mandate that utilities use a certain percentage of solar in their generation portfolios.

Why do renewable energy credits exist? Because you can’t tell one electron from the other. Coal, wind, sunshine, and gas all create electrons that are indistinguishable from each other.

What’s more, electricity doesn’t necessarily flow where you want it to go. Like drops of water, it all blends together and flows along the path of least resistance. That means electrons from a large solar installation may not go to the manufacturing business that wants to be able to tell customers they use 100 percent clean energy. It may power nearby households and business that have no green goals whatsoever.

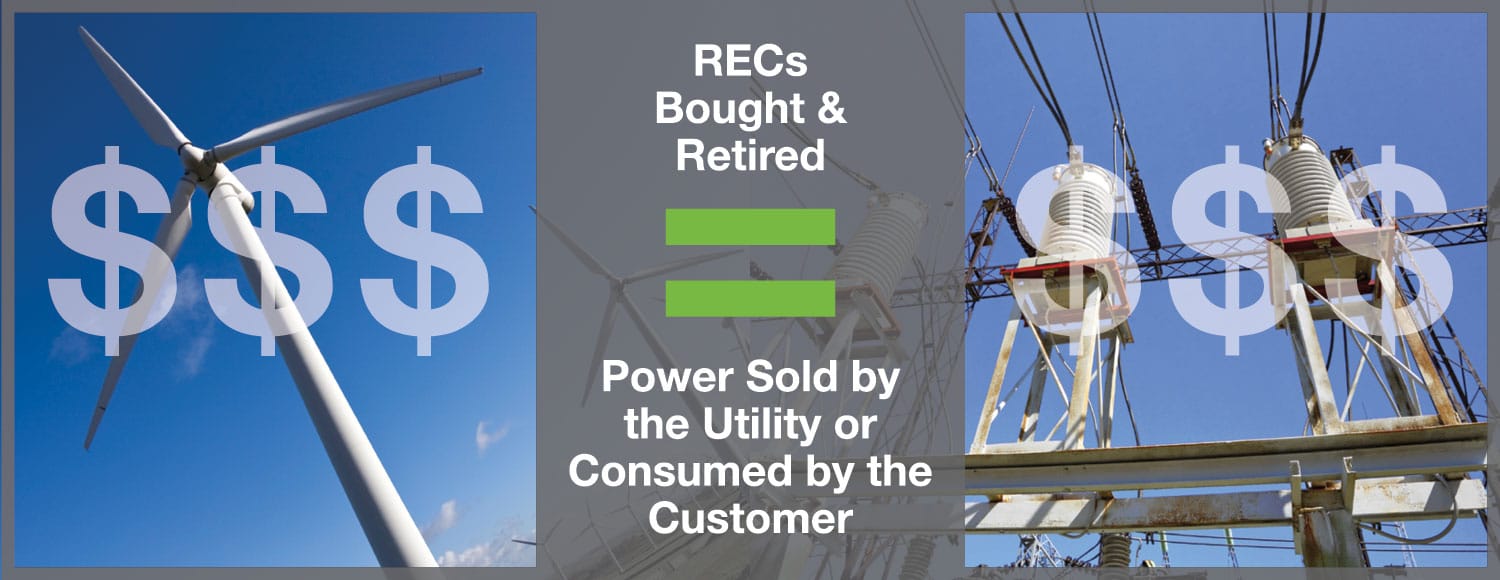

To maintain desired bragging rights, that manufacturer can buy renewable energy credits. Similarly, utilities that must meet renewable energy portfolio standards imposed by state lawmakers, and regulators also can buy RECs — and they do.

The party that buys an REC “retires” it, so it is no longer on the market and its environmental benefits can’t be claimed by multiple parties.

Energy journalist David Roberts explains the process this way in a Vox article: “When a utility says it is getting 20 percent of its energy from clean sources, what it means is that it has bought and retired a number of RECs equal to 20 percent of the power it sold. When a customer buys green electricity from a utility, what she’s really doing is paying the utility to retire a set number of RECs. When a business says it is ‘powered by 100-percent clean electricity,’ it means it bought and retired a number of RECs equal to its power consumption.”

Getting those RECs to market is a cumbersome process, note Creyts and Trbovich. One reason is because today’s REC recording and transfer processes involve multiple players.

Among them you’ll find the renewable generation plants themselves, regulators that use tracking systems to verify compliance with state portfolio standards, market intermediaries and, often, third-party verification agents such as accounting firms that validate the integrity of the information.

“This complex process results in relatively high costs and a time lag, often taking months to complete a transaction,” Creyts and Trbovich note. “This system, with multiple actors, processes, and data formats, is subject to several vulnerabilities, including unintentional accounting errors, double counting of certificates (including intentional abuse), and cyber theft or data manipulation. The result is a flawed and highly inefficient market that is difficult and costly to access.”

Block chain could be the fix. At least that’s the aim of companies participating in the Energy Web Foundation.

They’re not the only ones piling on with this new technology, either. Last October, Greentech Media ran a roundup of 15 Firms Leading the Way on Energy Blockchain, and the subhead on that article offered this premonition of breakneck growth. It read, “More companies will probably have launched by the time you read this.”